Tuhinga / Essays

Compilation of videos (duration: 14'16") played in the installation (Rachael Rakena and Brett Graham)

Āniwaniwa

Essay: Memory of Water

Author: Sean Cubitt

Year: 2007

Publication: Āniwaniwa catalogue, 52nd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia, Italy (PDF file, 20 pages, 785KB)

View Project

Where water and electricity meet, sparks fly. At Horahora, they took the power of the waters to make electricity for the goldmines at Waihi. You have to wonder at this marvellous alchemy, that transformed water into gold.

The mighty Waikato river, as it tumbles past, is named Aniwaniwa, a word that might be translated through an obscure but beautiful meaning of the English word 'glory', which along with all its other meanings, is used to describe the effect of a rainbow fringe appearing around a shadow cast on clouds, a phenomenon only witnessed by mountaineers and pastoralists for most of history until the invention of air travel. A radiant halo of light that comes from the play of the electromagnetic spectrum displaced and dancing in veils of water droplets, like a cloud halo round the moon.

What electricity we have that is not derived from the fossil remains of ancient forests and their denizens (and the tiny fraction from direct sunlight) comes from water, Aniwaniwa is a tribute to that transformation of flow from the liquid to the energetic state. In its organic sculptural forms it speaks of the cycle of matter and energy. Throwing the solid state of the mould into a relation with the flow of images raises new thoughts about stewardship and witnessing. Brett Graham's grandfather who tended the turbines on the Aniwaniwa witnessed and guarded the river's transformation into power. His grandson witnesses and guards in the feather-chest of his sculpture the transformation of water into images, and the holding of the flow of images in the sculpture's screen, like a river holds a feather up to the sun, like an engineer tends his machine, like a man tends a memory in the floodstream of his life.

The memory of water: how is it possible to remember the infinite variety of its ripples and curls? In Gaelic poetry, there is a form reserved solely for the praise of water: and this work has something of that form. But how to praise what is unceasingly unstill? And how to hold the memory of the element that is our shared metaphor for all that changes? Water's surface flickers and froths where it meets the wind. But under the surface, where we go so infrequently, there it is not a question of how a woman remembers water, but how water remembers us.

A river remembers not the waters that have run through it for all its thousands of years, but the shape of what is not the river. The riverbed and the riverbank are, to the river, the boundaries of its own native shape. Only when the storms rage and the river forgets in its fury, only then do the banks and beds dissolve, change shape. But everyday in the rapids, the river plays with its edges, throwing itself into the air, transforming itself from water into light.

The electricity of the camera and projector remember that leap into air. In the endless stream of images, where every image can be replaced with any other just like any drop of water, these images are kept in pools, in jars, in treasure boxes so that the memory of water and its bounty shall not vanish.

I like the edges where the projected light bounces from the lacquer. It sanctifies the light.

If water no longer knows its boundaries and swallows the coral atolls it has nurtured for so long; if the foreshore forgets its edges and rises, will the water recall the people of the sea? Gently the images teach water how to remember the people who have lived with it for so many centuries. Deep as the turbine drowned at Horahora, will water recall the shapes that entered it, that gave it new, living, diving, dancing forms inside itself? As Rachael Rakena teaches electricity to remember water in the form of streams of images, and as Brett Graham teaches the fluid formless fibreglass to remember the mould, these pools suspended in a gallery remote from rivers and seas remember, and teach remembrance.

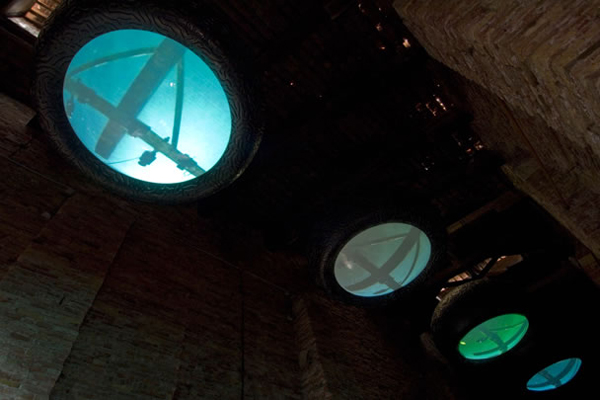

Like a sea-cave which has trapped bubbles of air in cavities in the rock ceiling, air that the water recalls in its pulsing and lapping, these inverted pools of electric water remember the shape of lives, projecting time as they invert gravity.

For water is the shape of time, time in all its tragedies and transformations, its living and its dying, its way of forever coming to birth. Sage heraclitus at the very dawn of writing knew that no-one could step into the same river twice, and yet the river, that emblem of life, is always the river, even if the river is never identical with itself. Just as the person who steps into it is the same person and yet changed, utterly changed.

It is time that we experience here, the strangeness of a treasure that is always treasured, even though it is never the same twice, treasured because it is never the same twice. The stillness of the box tells us of endurance, of the long memory of things. The fleeting images speak of the rippling ever-changing micro-geography of events as they occur within us and without.

There is no still point. Soft illuminations flicker at the lip of the curved carved forms, bounce from faces turned upwards to them, a corona at the interface between phases of the light, the water, the electricity, of time itself.

What is past comes back to us as the memory of all the ancestors accumulated in our 21st century technologies. Crowding round in the shape of things, the Western tradition has forgotten the names of its ancestors, burying them anonymously into the black boxes of cameras, projectors, tools, devices. In Aniwaniwa, the cruel technological trick of depriving the dead of their names and enslaving them is unravelled.

Time reversed in the upside down pools reflects the actions of ancestors perhaps as yet unborn, the last dance in the sea before the rising tides obliterate homelands, as they obliterated the town of Horahora. These memories are not only those of the ancestors past whose shapes water recalls, but those of the future dead, a remembrance before the event of an event we must fear even as we work to prevent it.

To live well, one must live with the world. This art is a lesson for people, for the green world, and for technologies, a lesson in how our memories are inseparably intertwined in the flow and ebb of time. Be still, throw back your head, attend to how the present is the moment in which the past and the future alike come to birth.

View the Āniwaniwa catalogue, 52nd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia, Italy (PDF file, 20 pages, 785KB)