Tuhinga / Essays

Moengaroa

Essay (1 of 2): Bathroom and Bedroom Politics: The Black and White of It

Author: Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, Dean of Music and Fine Arts, University of Canterbury (Christchurch, New Zealand)

Year: 2002

Publication: Moengaroa catalogue (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, New Zealand)

View Project

For the artist-in-residence, the first task was to take stock of the immediate environment and try to make sense of the place. What was the relevance of Switzerland-the Southern Alps" near antipodes, in fact – for a politically focused young Māori artist so far from home – Graham's information-gathering uncovered some promising material about formative influences on European attitudes to race which to this day cast dark-skinned people into the role of "other". Jean-Jacques Rosseau, the moralist whose concept of the uncomplicated "noble savage" living in harmony with Nature gained wide currency in later eighteenth century Europe, was Swiss in origin, as was John Lavater, the proponent of the long since discredited, racist pseudoscience of physiognomy, in which character was judged from facial features. John Webber, the official artist on James Cook's third (and fatal) voyage to the pacific, was also of Swiss parentage.

Scuol has been, in the nineteenth century, a fashionable health spa to which Europeans flocked to "take the waters". In the grounds of the large hotel built in the 1860s (parallel to the Waikato land confiscations, the artist notes), stands a palatial residence built in anticipation of a visit from Queen Victoria (in whose name the Treaty of Waitangi, the "marriage" between Māori and the Crown, was, in 1840, solemnized). Graham found his living quarters in the bathhouse "sterile and white, almost asylum like". His response to these clinical surroundings was to create from coal an overscaled bath. "Coal, he explained, "is dirty and blackens everything it touches, it references racial slurs, yet is of the earth". Ironically, it is from coal that black coal-tar soap, a legacy of Victorian science and industry, is manufactured. The product was originally marketed with humorous "coon" and "nigger" images.

Back home in Auckland, Brett Graham has moved, metaphorically, from the bathroom to the bedroom. These are the most private and intimate enclosed living spaced in our domestic environment. When we submit our bodies to cleansing routines, when our consciousness is almost suspended in sleep, we are at our most vulnerable. The bed, in addition to its primary function as a place of rest, is associated with nuptial consummation, conception, birth, convalescence and death. It can also be a place of domestic violence and sexual violation. The marriage bed in Shakespeare's Othello is a site of miscegenation and murder. Bending over his sleeping wife, the "Moor of Venice" momentarily hesitates to "scar that whiter skin of hers than snow and smooth as monumental alabaster" before smothering the blameless Desdemona with a pillow. Sin is black; moral (and by implication, racial) purity is white. (1)

Stark, shocking and apparently irreconcilable differences between blackness and whiteness delineate the racial and moral divide that Brett Graham critiques. In the permanently colonized condition of Māori, "creature comforts" of "civilisation" such as the pillow, the bed and the white sheet loom as emblems of cultural genocide. Anticipating the rapid demise of Māori towards the end of the nineteenth century, Sir Walter Buller supposed that the colonists" role was to "smooth the pillow of a dying race..." In such a scenario the bed becomes a bier, the sheet, a shroud.

Tension between the descendents of the colonizers and the colonised persists to this day. But, as Ranginui Walker observes, "the differences from our Colonial past are being settled in the bedrooms of the nation". (2) Just as the bedroom operates as a zone of assimilation in an ideologically bicultural nation, so the bathhouse might signify "ethnic cleansing". In 1889 an advertisement in McClure's Magazine depicted a naval admiral in the act of washing his hands. "The first step towards lightening The White Man's Burden', (3) the advertising copy reads, "is through teaching the virtues of cleanliness. Pear's soap is a potent factor in brightening the dark corners of the earth as civilization advances..." In the eighteenth century John Wesley preached that "Cleanliness is, indeed, next to Godliness". (4) Cultural whitewash could be said to be one of the tragic consequences of European Colonialism and Christian imperialism on the colonized indigenous "other".

(1) But see "I am black but O! my soul is white" (William Blake, The Little Black Boy)

(2) Ranginui Walker in Metro, February 2001 in the essay Hostages of History

(3) The title of an excruciatingly jingoistic and racist poem by the most imperialistic of all Victorian poets: Rudyard Kipling

(4) Evangelical posters in the 1950s, in a parody of washing powder advertising hype, proclaimed, Jesus washes whitest of all

Essay (2 of 2): If You Delve Deeply Enough Things Will Declare Themselves

Author: Ngahiraka Mason, Indigenous Curator Māori Art

Year: 2002

View Project

Brett Graham is a serious and "cool" personality-as in Māori film director Lee Tamahori meets Wellington's fine-act band Trinity Roots' cool. A traditionalist when it comes to explaining things to his audiences Graham likes to prove things to himself. A high achiever and model child, Brett is confessional, in a caring way.

His knowledge and practice of Māori concepts such as manaaki (putting others first) are exemplary. Graham is outstanding at extrapolating tough conflicts and emotions, because to him, feelings are strong things. His recent art explores pre-quel and sequel events in New Zealand's social history and if you delve deep enough, things will declare themselves. All "cultural developments" come filled with struggle, surreal outcomes, love, tragedy, celebration and loss, and Brett Graham's art explores all of these issues. Although Colonial history is psychologically murky from an indigenous perspective, that which emerges from the shadows might actually present as hope for a yet-to-be-spoken-about future.

The terms indigenous Māori and Pakeha (a white New Zealander descendant from Colonial settlers) are distinct to Aotearoa New Zealand. They identify two groups of people that are inextricably linked-stuck with each other for better, for worse. For the most part conflicting but self-preserving social and political ideologies have driven Māori Pakeha relations to many extremes. Add Colonial Government assimilation policies and New Zealand's peculiar style of biculturalism to the association and the country's social and political fabric starts to question everyone's identity and world-view. Some New Zealand made films that speak to this burden in differing ways are the part-documentary, part-constructed and part-authenticating productions such as The Piano 1993 (Director Jane Campion), In Spring One Plants Alone 1081 (Director Vincent Ward), Heavenly Creatures 1994 (Director Peter Jackson) and Once Were Warriors 1994 (Director Lee Tamahori).

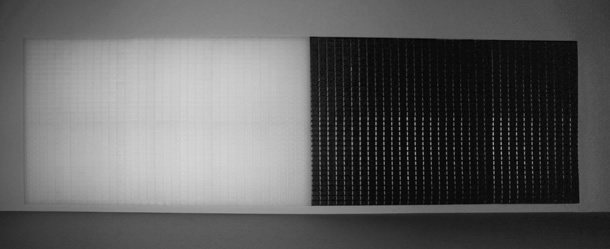

Moengaroa (eternal sleep) comprises a dramatically lit bed, pillow and sheet made from moulded plastic designed to look like soap. Graham's rendition of the sheet is a large light box which sheds light on the over-writing of indigenous place names that were replaced with Europeanised Pakeha ones, which Brett has accurately recorded, and studied obsessively. Similarly, the oversized king-bed lays bare the clear split of a bi-racial heritage, which represents New Zealand's particular style of biculturalism. The moulded pillow – a less than smooth headrest – completes the installation. But, is Graham presenting a site which Māori and Pakeha would like to crawl-out-from-under?

The entry points to Moengaroa are laden with emotional layers, some that can't be seen, such as the everyday realities and pressure to be bicultural. Graham's focus is a combination of integrations and adaptations that require huge emotional investment by him. By staring "biculturalism" in the face he is clearly someone who has an unflagging quest to investigate race as a powerful agency. He has carried his investigations even further by shifting from his comfort zone and use of traditional materials such as wood and stone to the newer material of plastic. Then again, Graham's use of plastic materials can be read as a pledge to set his practice in motion in other ways.

Moengaroa is both cynical and hopeful and, to some extent ambivalent. The project deliberately revives old territories that are an accumulation of both put-downs and accolades to do with Māori identity and New Zealand nationalism. Less encouragingly, the title has uncertainty about it, for to speak of Moengaroa is to stand before a tupapaku (deceased person) and pay tribute to and recount the life of the loved-one, farewelling them onto the next world.

While the politics of questioning is not exclusive "questioning" is more easily rejected and misunderstood, rather than comprehended. Making meaning of race, identity politics and Colonial history is daunting. For all New Zealand's social, cultural and political stumbling, Moengaroa provides a meeting point that is challenging, exposing and directional. Which can lead to a place that considers the future in-depth and opens up thinking. As you make your bed, so you must lie on it – everyone must bear the consequences of his own acts.